By: Amit Roy

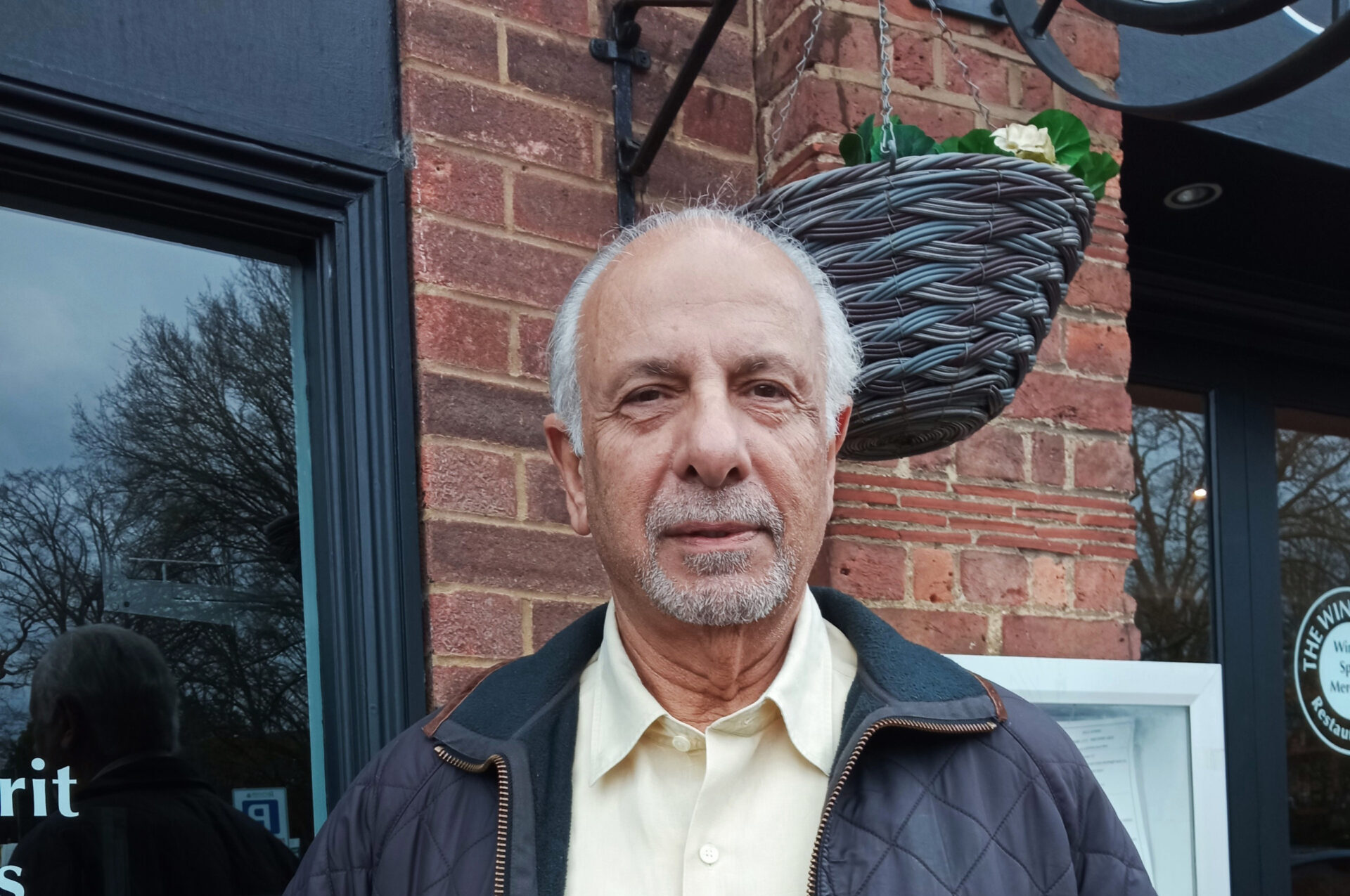

ENTEPRENEUR Dinesh Dhamija has told Eastern Eye he wrote The Indian Century because he wants the 30 million-strong Indian diaspora across the world, but especially in the UK, to invest back in the mother country.

The interview about his new book, in which he gives an upbeat assessment of the Indian economy, takes place near his home in Virginia Water, described as “a commuter village in the Borough of Runnymede in northern Surrey”.

It is a scenic part of the world showing the first signs of spring. By the station is a sign indicating a riverside walk. Dhamija has arrived casually dressed, but chauffeur driven in one of his Tesla limousines with a personalised number plate.

He says he put in “a bit of money” into an Indian investment in October 2022, and “till the first of this month earned a return of 37 per cent. Where else can you get that?”

He is encouraging the 2.5 million people of Indian origin in the UK to follow his example.

To give Dhamija his due, when it comes to making money, what the entrepreneur says has to be treated with respect. He is, after all, the pioneer who had the foresight to develop online booking for travel. He put his story into his debut book, Book It! How Dinesh Dhamija sold travel agency ebookers for £247m.

He reiterates that he wrote The Indian Century “because I want the diaspora to start investing in India because the market is growing and everyone is going to make a lot of money.”

What about putting in, say, a few hundred pounds?

He nods.

It could be done through brokers or going direct to the companies in India. He mentions the BSE Sensex, “a free-float market-weighted stock market index of 30 well-established and financially sound companies listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange”, or the Nifty 50, “a benchmark Indian stock market index that represents the weighted average of 50 of the largest Indian companies listed on the National Stock Exchange”.

“So 30 plus 50, that’s 80 companies (where people can invest),” he says. “Say you put in £1,000, which becomes £3,000 by 2030, which isn’t bad.”

What made him think about the diaspora was the Chinese example. Investments b y overseas Chinese had helped transform the economy of China. He agreed with Narendra Modi when the Indian prime minister announced his “Make in India” policy.

Not that Dhamija is uncritical of the Indian system. He finds it totally unacceptable that in the Indian legal system, court cases routinely take 20 years to resolve. This, he implies, puts off potential investors.

“I am not saying India is a bed of roses. I am pointing out these problems need to be solved by Indians in India. Then, instead of $100 billion coming in in overseas investments, the figure would be closer to $500bn.”

At the moment, there is no sign that the UK and Indian governments are ready to conclude a Free Trade Agreement. Dhamija reckons progress has been slowed down by a clash of “egos”. But if an FTA were to be signed, “it would mean the creation of 300,000 new jobs in the UK and a million new jobs in India”.

He studied trade deals when he was head of the India desk during his brief spell as a Liberal Democrats Member of the European Parliament (MEP) in Strasbourg in 2019. “The experience of the European parliament is that exports double as the result of a trade deal.”

According to the World Bank, India’s economy, currently worth $3.7 trillion, will grow to $7tn by 2030. By that reckoning, the per capita income will go up from $2,200 to $4,000. But Dhamija calculates the true figure will be closer to $10tn when the ‘black’ economy is taken into account.

He talks about one of the chapters in his book, “Cricket as a Metaphor”, and says: “I am not here talking about the results of cricket matches but, financially, India controls the world of cricket. And if you excel in cricket, you can excel in other things – that’s my take.”

Dhamija was born in Australia (where his father was posted as a senior Indian diplomat) on March 28, 1950, attended Mayo College in Ajmer, Rajasthan, followed by St Xavier’s School in Delhi, and then went to the King’s School, Canterbury, before Cambridge.

He read Oriental Studies in Part 1 followed by Law in Part II when he was an undergraduate at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, from 1971-1974. He has been elected a “Benefactor Fellow” of Fitzwilliam, having gifted £1m to his alma mater “to increase the college’s capacity in teaching and research across disciplines of applied engineering and science”.

He is currently working with the Judge Business School at Cambridge on a programme under which the high flyers who belong to the Young Presidents’ Organisation pay £9,000 to hear insights into four areas – the human body, machines and robotics, AI and space.

Dhamija has now invested heavily in solar energy and green hydrogen plus real estate in Romania.

The Indian Century concludes by looking at what the country might be like in 2047. “As anniversaries go, 75 is all very well, but 100 is the big one,” writes Dhamija. “After a century of independence, India will really be in a position to assess its successes and failures.”

“Everyone is acutely aware of this looming milestone from the prime minister downwards. Deloitte anticipates India growing to become a $17tn economy.

“India will be a $26tn economy,” forecasts consultancies PwC and EY, while the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) goes for an impressive $35tn-$45tn.

“Whatever the future, India in 2047 is likely to be a hugely different country from that in 2023, never mind that of 1947 when it had a population of 340 million, 20 per cent literacy and a life expectancy of 37. Today’s 1.4bn are 80 per cent literate and live to more than 70.”

Dhamija does not avoid risk factors.

“Among the general euphoria over the likely size and power of the Indian economy and national prestige in 2047, there are few voices of dissent,” he goes on. “It seems unpatriotic to disagree with uplifting visions of showering wealth, unending technological progress and relief from poverty. But we need to remember, a good friend is one who tells the truth, who warns of danger. Even in a scenario when India becomes a $20-plus trillion economy in the 2040s, how that giant pie is divided makes a difference. Oxfam recently found that 1 per cent of India’s population controls 40 per cent of its wealth and that the bottom half has just 3 per cent. If that disparity continues, or widens, the benefits to India as a whole will be marginal and its potential to become ‘developed’ will remain unfulfilled.”

Inspired by his late father-in-law, General Om Prakash Malhotra, who was chief of the armed forces of India, Dhamija helped set up two charities near Delhi. Chikitsa (meaning treatment in Hindi) provides free medicine to 120,000 people through 15 clinics in and around Gurgaon, where a great deal of construction works has been going on. Another charity, Shiksha (education), provides free schooling to children in three school buildings.

“They are given a good meal at lunch – probably the only meal they will get during the day,” he says. “We also have a blind class as my father-in-law was head of the Blind Association of India.”

The charities are now run day to day by his nephew, Uday. “I started off with putting $250,000 in each charity. But it’s not enough just to given money. You also need organisational talent.”

The Indian Century by Dinesh Dhamija. Finito Publishing. £19.99

[TheChamp-Sharing]

[TheChamp-Sharing]